Alan Chadwick's Character

“It has been my experience that folks who have no vices have very few virtues."

― Abraham Lincoln

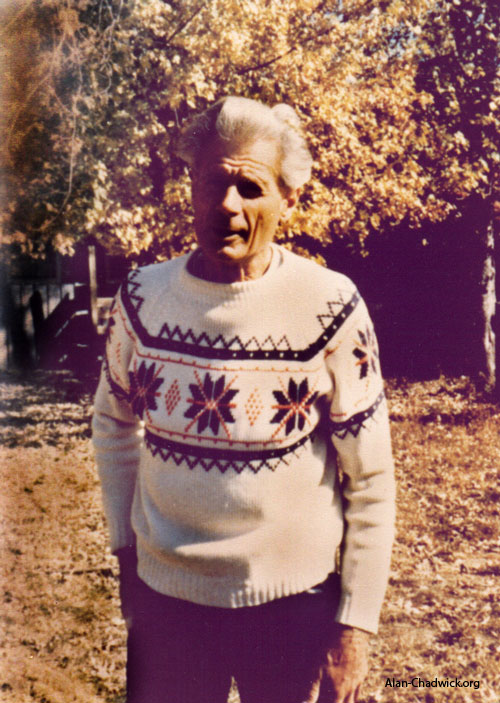

Alan Chadwick had a great many outstanding qualities and talents to share with the world, and for those who knew him well, these mostly eclipsed his more minor failings. The collection of personal memories, anecdotes, books, lectures, and commentaries about him on this website offer extensive accounts of his extraordinary character.

As a consummate artist and onetime Shakespearean actor Alan Chadwick was creative in every aspect of his life, enlivening the atmosphere around him with theatrical flair. His charming openness made him particularly charismatic, and this was further magnified by his profound eloquence, enriched by poetry, music, and humor.

To those who could see beyond his sometimes gruff exterior, Alan was uncommonly gracious, thoughtfully responsive, sensitive and respectful. His experience as a naval sea captain during World War II fostered an already adventuresome spirit, but also added a Spartan quality to his nature, wherein he was confident, courageous, energetic, and authoritative.

Alan was a highly intuitive, even visionary individual who had a keen sensitivity to the inner nature of those around him. His compassion for others often took the form of honest and forthright challenges to their current level of maturity and capacity for growth. Because he had the fortitude and inner strength to confront his students on their most sensitive points and weaknesses, he could prod them onward toward higher levels of self knowledge. Most people react with instinctive hostility to unwelcome truths, and therefore few teachers are willing to provide this kind of guidance. But more than anything, he taught by example: Being himself physically strong, mentally acute, competent and resourceful, he could demand the same from his apprentices.

Toward nature Alan was keenly observant and deeply reverent. He was trusting to a fault and had full faith in the wisdom of providence. Persevering and willing to suffer for a just cause, he held himself to exceedingly high standards. As an independent thinker, he manifested high aesthetic values that few others could even conceive of. His knowledge and wide experience made him uniquely competent to realize his visions and inspirations to an exacting degree.

All these traits were what attracted and inspired his many apprentices to elevate their own lives and discover ever more creative forces within the world. Many students were deeply transformed by the experience of working with Alan, and afterward found the incentive to undertake ambitious social and environmental projects of their own.

Alan also had a mischievous love of practical jokes, which could be seen either as positive or negative perhaps, but these were never mean-spirited or detrimental, even though being on the receiving end was not particularly enjoyable.

His penchant for the dramatic could also be seen as a mixed blessing. Indeed, after a while the recurring stream of overly-charged pseudo-cataclysms took an exhausting toll on Alan’s students. But then, on the other hand, this tendency also served to elevate the hum-drum daily routine to a level where it became memorable and significant. For what is drama but the focus of one’s attention on the deeply meaningful and momentous aspects of life, rather than on the purely mundane? The poetic and theatrical arts carry us to a higher threshold of consciousness where the temporal meets the eternal.

This should not be underestimated: The human being has evolved to respond to such core cultural motifs. Religion, art, philosophy, and even historical analysis, are all examples of human beings trying to make sense of their earthly predicament. Alan elevated work that might otherwise have been experienced as dull and plodding drudgery into a social cause that aimed at saving the earth and transforming human consciousness. Those of us in Chadwick’s gardens knew that we were on a mission to rescue the human spirit from the tyranny of scientific reductionism and soulless materialism. Beauty, for example, can make the difference between joy and despair in the human spirit. It has an essential place in life even though it cannot be weighed or measured in the chemist’s balance scale, and we felt that we were its champions in this dark age.

There is no question Alan Chadwick clearly had his faults too, even though these were largely outnumbered by his many virtues. As best and as much as I can recall the full picture of his personality, considering both his positive and negative characteristics, only a few vices come to mind, but one of them at least, was prodigious: Alan had a very tempestuous temper. Little things would set him off, and then an avalanche of pent-up frustrations could be unleashed on the unlucky recipient of his wrath.

Of course, there were mitigating circumstances that help explain why this should be so. Physically, emotionally, and financially, Alan was always right on the edge. Physically, the triple back-injury that he suffered during World War II is the most obvious factor, as this caused him to frequently experience intense spasms of excruciating discomfort. He would be standing, smiling, describing some aspect of plant culture, and then suddenly without warning would shudder violently and let out an agonized gasp of pain. Anyone who has ever experienced chronic pain of this type knows that one’s equanimity is put severely to the test under such circumstances. Later, during the Covelo Project when Alan became ill with cancer, the effects of physical pain on his temperament were greatly intensified.

Another factor is that Alan felt very emotionally isolated. Every day he contended with people who wanted something from him: either students who wanted his knowledge, or other people who wanted the produce of the garden. There were always problems with the University administration, or later with the officials at the Zen Center. It was never ending, and Alan had to face it all alone. For whatever reasons, he was never quite able to form the kind of stable personal relationships that others enjoy and which would have supported him emotionally in the midst of life’s relentless demands. According to Alan, T. E. Lawrence, the famous English writer, was the only person who ever really understood him. Later, he was very close to Freya von Moltke in South Africa, and perhaps might have married her if he hadn’t one day suddenly suffered one of his symptomatic rages in her presence, and thus ruined the opportunity.

Alan was also very much an idealist, and this took its toll as well. When Freya persuaded him to accept the task of sharing what he knew about life and horticulture with the lost youth of America, conceiving and executing the famous gardens at Santa Cruz and Covelo, Alan took it on like it was a spiritual commission. He set aside his own personal interests to the greatest extent possible, investing all of his resources in the creation of the garden. When the University provided him a modest salary, he divided it up and shared it with four experienced apprentices who could then form a support staff to keep things going. The gardens at that time were far too much for any one person to manage alone, and so this sacrifice was necessary—but it also stretched him to his limits financially.

Later, he was always economically dependent on his sponsors and benefactors, and this inevitably caused a strain on his sense of independence. He reasoned that, if he gave everything he had to the cosmic forces of goodness, truth, and beauty, then in return the cosmos would and should reciprocate, meeting at least his very basic physical needs. This actually did, more or less, come about, but at times he was severely put to the test and forced to endure exceedingly trying circumstances.

It also cannot be denied that the experience of having been betrayed and expelled from Santa Cruz took a severe toll on his optimism, faith, and health. A younger man can easily recoil from such events, but Alan was sixty-three when they turned him out of the environment that he had spent five years creating there. At that age, a man does not have many five-year periods left to invest in building up something valuable out of nothing. He made the best of the situation, as his subsequent work was a meaningful contribution to the discipline of sustainable agriculture. But one can only imagine how much more productive he would have been had the retrograde forces of opposition not prevailed at that time.

Despite his limited income, he was generous to a fault: When there was no more grain for the animals in the garden at Santa Cruz, Alan would write a personal check so that more could be bought. Once, when a teacher from a nearby continuation high school asked his help to establish a school garden for his students, Alan declared that he could hardly maintain the garden that he had, asking if any one of us apprentices would be willing to help the man. When I volunteered, and later asked him if the garden budget could afford to buy enough gardening tools for the new project, Alan unhesitatingly whipped out his personal check book and gave me sufficient funds to buy spades, forks, and rakes for twenty students.

In addition to these major constraints affecting his peace of mind, Alan was also hyper-sensitive to the abuse that the natural world is forced to suffer on every side from insensitive human beings. It is not difficult to understand why he was frequently prone to exasperation. Steve Decater points out in a video interview on this website how Alan had aligned himself so closely with the natural world that he personally suffered whenever nature suffered. If, when riding his bicycle up the road to the University, he encountered a meadowlark that had been killed by an insensitive motorist driving at an unreasonable speed, he would become beside himself with indignation. “Just let one of these bloody fools try to make anything as beautiful and magical as one meadowlark,” he said, “and they will find that they are utterly impotent. All they know how to do is destroy.”

Another time, I observed a friendly visitor speaking to him on the chalet deck at Santa Cruz. During the course of the conversation, the man began absentmindedly to pull the leaves off of a bamboo that Alan had planted near the entrance to the deck. One after the other he plucked them until he had ripped six or seven bamboo leaves off their stems. Alan controlled himself to a far greater extent than I have ever seen him do, either before or since. He interrupted the gentleman, softly asking him if, perchance, he didn’t like that particular specimen of bamboo? The man paused, noticing for the first time what he had been doing, and then blurted out a surprised and slightly indignant apology.

Whereas most people are oblivious to the pain that plants, animals, and even the soil, suffer at the hands of unthinking individuals, Alan experienced a profound inner pang that caused him to cry out in defense of the natural world. People were often offended by his angry reactions to their cruelties and unconscious barbarisms, but Alan was speaking for the world of living beings that has no voice of its own. On some level, he also cared enough about humanity to think that if he could finally wake up any given person, then he or she might, through a personal transformation, become an ally to the world of nature instead of an adversary to it.

Besides his temper, Alan had a few other vices. For example he could be spiteful and conniving at times, even catty. He would occasionally pit one apprentice against another so as to hold the reins of power in interpersonal relationships. This he primarily accomplished through conferring praise or disapproval, as everybody worked hard for approval and earnestly tried to avoid Alan’s displeasure. He was a powerful individual who could see through most people’s motives, and from time to time he would exploit that talent for his own reasons. These episodes were not common, by any means, but they happened just enough to warrant notice of this particular weakness in his character.

Alan also had a tendency to play the martyr. I can remember him saying things like, “Everybody just comes through here taking what they want, never giving a thought to what it takes to produce it. I never get one iota of appreciation for creating this whole bloody place.” On one occasion Christina Gibbs, the Student President of the Garden Project at the time, and I successfully preempted that tendency by presenting him with a bountiful gift-basket. It was a show of appreciation that was also calculated to curtail any more of that kind of “poor me” attitude. After our grandiose gesture of gratitude in the summer of 1971, I never heard Alan play the martyrdom card again on any of his followers.

Regarding those individuals who try to malign Alan Chadwick’s character by complaining solely about his temper, they mostly succeed in exposing their own shallowness and lack of vision. It’s as if someone were to offer you a valuable nugget of gold on the condition that you fetch it from the top of a nearby mountain. Do you appreciate the gift, or gripe about the hike? Unfortunately, human nature is all too often prone to display the latter trait. As Mark Twain quipped,

“If you pick up a starving dog and make him prosperous, he will not bite you; that is the principal difference between a dog and a man."

Justice, on the other hand, compels us to acknowledge the generosity of our benefactors while they live, and to honor their memories after they are no longer with us.

— Greg Haynes, August, 2013